The Battle of Red Cliff

Sources and Further Reading

WorldHistory.org

WorldHistory has a good general overview of the battle of Red Cliff.

PatrickSiu.org

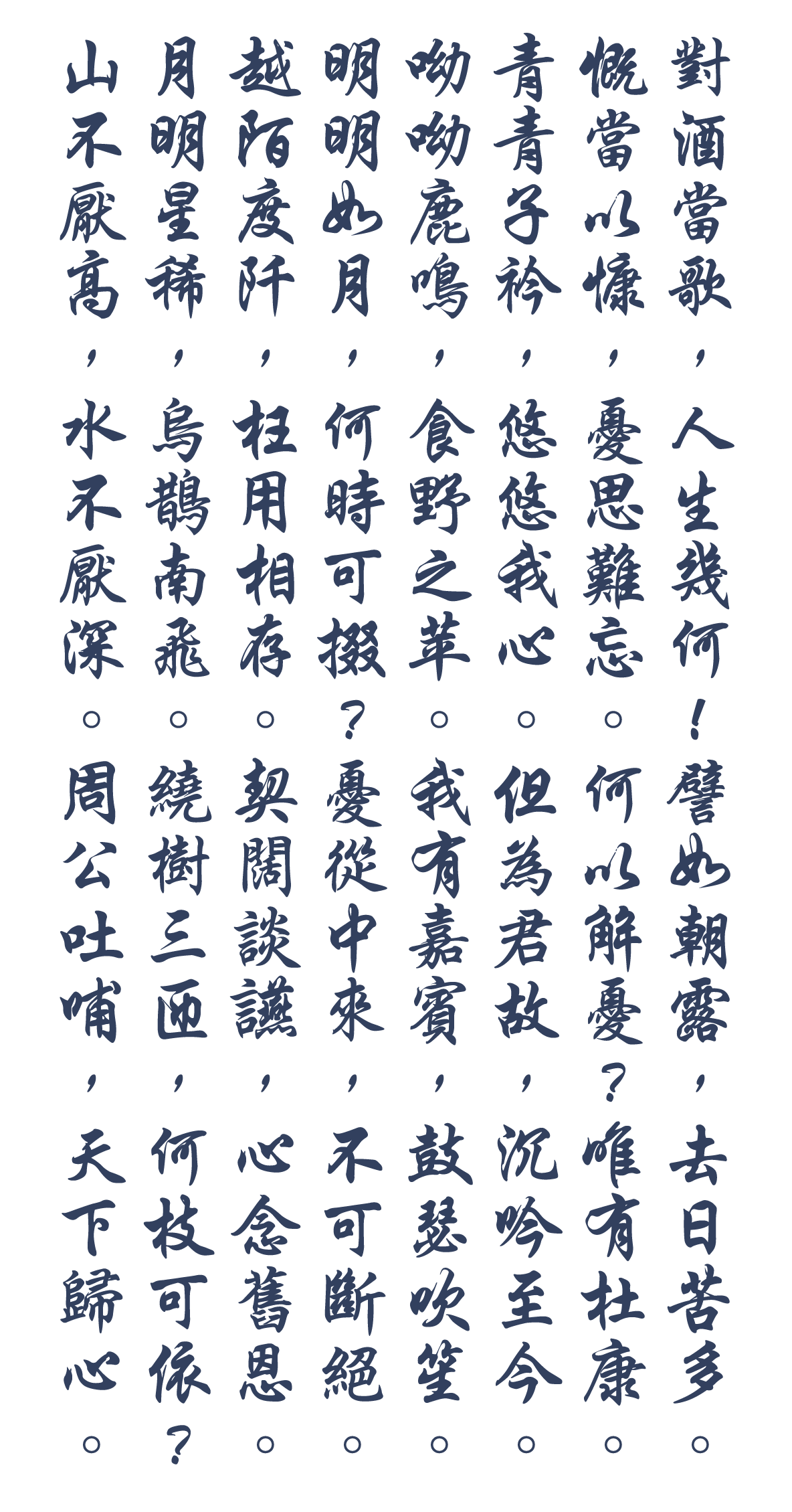

This well-researched personal website has reproductions of Su Shi’s First Ode on the Red Cliffs, including a side-by-side translation and commentary on calligraphy.

https://patricksiu.org/first-ode-on-the-red-cliffs-qian-chibifu-

Arteeducation.com.tw

[中文] The text of Cao Cao’s poem, with explanatory notes.

https://www.arteducation.com.tw/mingju/juv_a641990b139e.html

Xue, Lei. “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial: The Nelson-Atkins’s Red Cliff Handscroll Revisited.” Archives of Asian Art 66, no. 1 (2016): 25–49. doi:10.1353/AAA.2016.0011.

This paper discusses some of the cultural resonances of Red Cliff, looking in particular at handscroll depictions of Su Shi’s visit to Red Cliff.

Paper available here

Yu-chih Lai, “Historicity, Visuality and Patterns of Literati Transcendence: Picturing the Red Cliff,” in Shane McCausland and Hwang Yin eds., On Telling Images of China: Essays in Narrative Painting and Visual Culture(Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013), pp. 177-212.

More discussion of Su Shi’s visit, cultural associations and representations in art in the centuries that followed.

Paper available here

An Anthology of Chinese Literature

Edited and translated by Stephen Owen

W.W. Norton & Company inc. 1996

See page 292 for a translation of Su Shi’s The Poetic Exposition on Red Cliff and page 664 for a biography of Su Shi and a selection of his works.

China Between Empires: The Northern and Southern Dynasties

Mark Edward Lewis

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press 2009

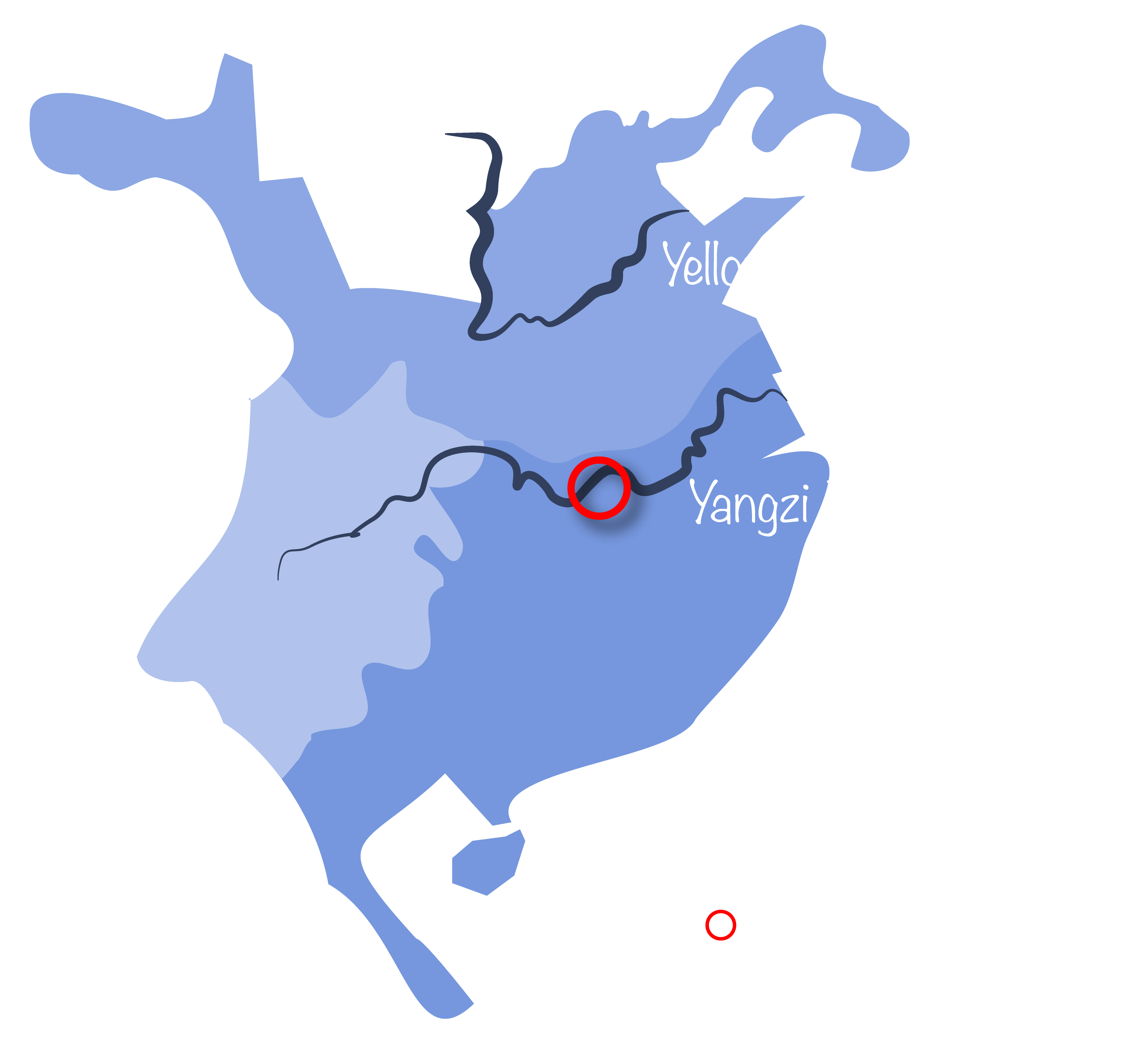

In particular, see the introduction for a discussion on Lewis’ choice of the term ‘Northern and Southern Dynasties’ for the four centuries following the collapse of the Han State. In short, he points out that it was a split between the two river basins of the Yellow River in the North and the Yangzi valley in the South which was to define the trajectory of China’s cultural and political history in that period.

Illustrated History of China

Patricia Buckley Ebrey

Cambridge University Press 1996

Red Cliff (赤壁)

Dir: John Woo

Magnet Releasing